Spike Jonze has certainly etched himself as one of the more creative and influential directors of our time. Bread in the new school of self-taught auteurs, Jonze has created his own compelling brand of cinema, placing offbeat characters in realistically tender scenarios. But the true stamp of a Spike Jonze film is his touches of magical realism that elevate his works beyond bizarre pieces and force his audience to constantly engage with his films.

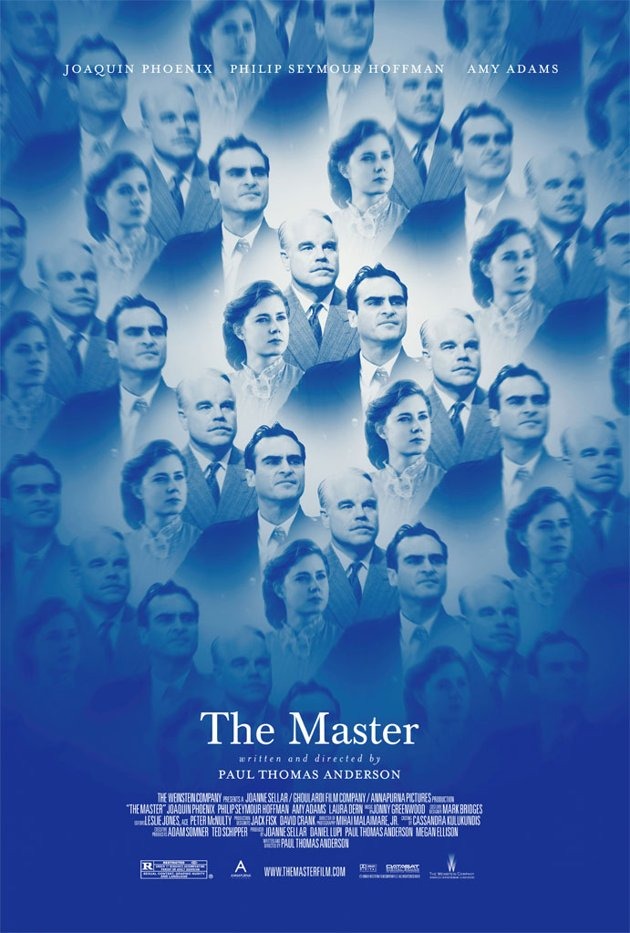

It is this ability to navigate and bend genres that allowed Jonze to draw such artistry and poignancy out of a premise as strange that in Her. It’s what can described as a Redditor’s fan fiction, Her depicts the lonesome Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix The Master, Walk the Line) and his budding relationship with his artificially intelligent OS Samantha (Scarlett Johansson, The Avengers, Captain America: Winter Soldier).

In the hands of a lesser writer or director, the film could have easily been cheapened or become farcical. Jonze, however, maintains a steadfast hand over his film and script. From the warmth of the pink-kissed color palate to the wistful score featuring Karen O’s “Moon Song,” Jonze creates an atmosphere built on trust and vulnerability. Even as he moves his film into more emotional intensity, he never betrays his audience’s investment, and treats his material with severe yet sincere reliability.

The film is buoyed by strong performances by it’s two leads. Even though Johansson is only a voice, the chemistry between her and Phoenix is palpable. The two performances complement each other perfectly, with Phoenix’s touching physicality and Johansson’s melodic tenderness. Both are halves of a beautiful dissection into a relationship.

Their relationship is set against a delicate picture of the future. In both costume and aeshetic, the Her universe seems like a realistic extension of our modern technological framework. It’s the perfect balance between futuristic predictions and muted change that creates just the right feeling of normalcy for its tale.

Her is a rare type of film with the unique quality of taking a step back from reality to take a closer look into it. We see ourselves in the best and worst of Theodore and Samantha, making us ponder and reconcile the choices we have made in interacting with others. That maybe the best solace doesn’t come from other people or gadgets, but somewhere in between. Someone like her.