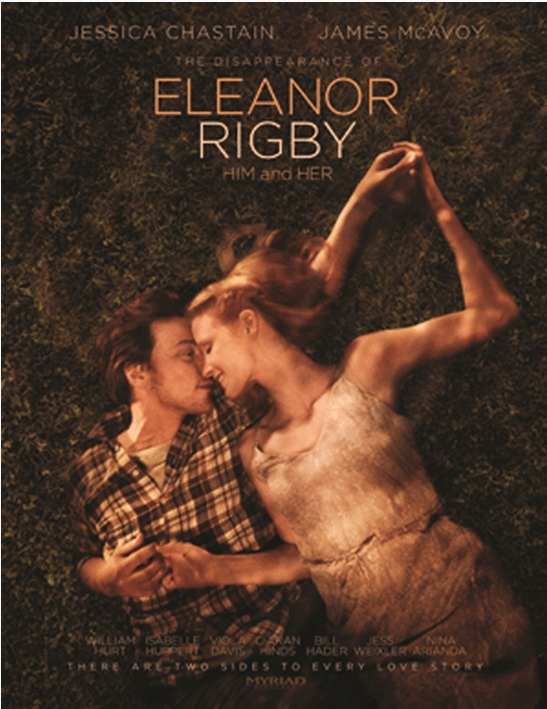

As Eleanor Rigby (Jessica Chastain, Zero Dark Thirty, Lawless) walks across the bridge there’s clearly something amiss. We don’t know what, but as she casually leaves her bike and continues her pace out of frame it’s the startled yell of a passerby and a faint splash that tells us where she ends up. We still don’t know why, even as her husband Conor (James McAvoy, Trance, X-Men: Days of Future Past) rushes into her hospital room, only to find her asleep.

It’s the audience’s beginning tug on the sweater of Eleanor and Connor’s marriage, chronicled in the “Them” chapter of “The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby.” Originally slated as two movies, (called “Him” and “Her”) they’ve since been recut into one.* It’s a slow-boil that recounts the couple’s story, especially as they study the shards of their relationship without an obvious focus. Eleanor returns to school, moves in with family, and refuses to even discuss Conor. In turn, Conor picks fights as he obsesses over his failed marriage and his failing restaurant business as he moves home to his own father’s house.

There’s an elegance to the way first-time director/writer Ned Benson frames the story. Though it may be quiet and unhurried — often taking its time to show off its cinematography skills as it circles backward and forward through time — it speaks volumes about processing grief, love, and how different expressions of those. The whole thing gives a sense of intricate plotting, but still carries the heavy burden of authenticity behind its emotion.

The film owes a lot to its lead actors, who carry their characters with a kind of unassuming heartbreak. They’re equally developed, whole characters with flaws and negativities that simultaneously balance each other out while also feeding on the other’s self-destruction.

As companion pieces Benson could’ve made a theatrical statement; the man vs. the woman, Kramer vs. Kramer, the variability of “Clue” meets the emotional nuance of “Boyhood.” But as a fusion, the result is a beautiful contrast between two volatile adults.

Though their problems may, at first, reek of advantage, of well-off, white, New Yorkers who can afford to take a step back from their lives, there’s a reserved sorrow that’s subtly woven throughout the film that everyone can relate to. The ethereal air of going through the motions after trauma and searching for something next to normal creates a reverent tone from start to finish, until finally the screen fades to black, and you’re stuck waiting for him and her.

*There’s talk of these being released to art house theaters soon/already, if you’re in New York. But there’s no word of it in Seattle yet. Once it does, expect a Deja Review from us, because when I found out this wasn’t based on a book I felt robbed of experiencing this story more.