Paul Thomas Anderson is a master of cinema. Watching his films, you can instantly tell he is a student of film, not a film student. Each of his films thus far (Hard Eight, Boogie Nights, Magnolia, Punch Drunk Love, There Will Be Blood) is constructed like a great novel; densely constructed with precision, complexity, and a severe sense of humanity. The Master joins his already prolific canon masterworks.

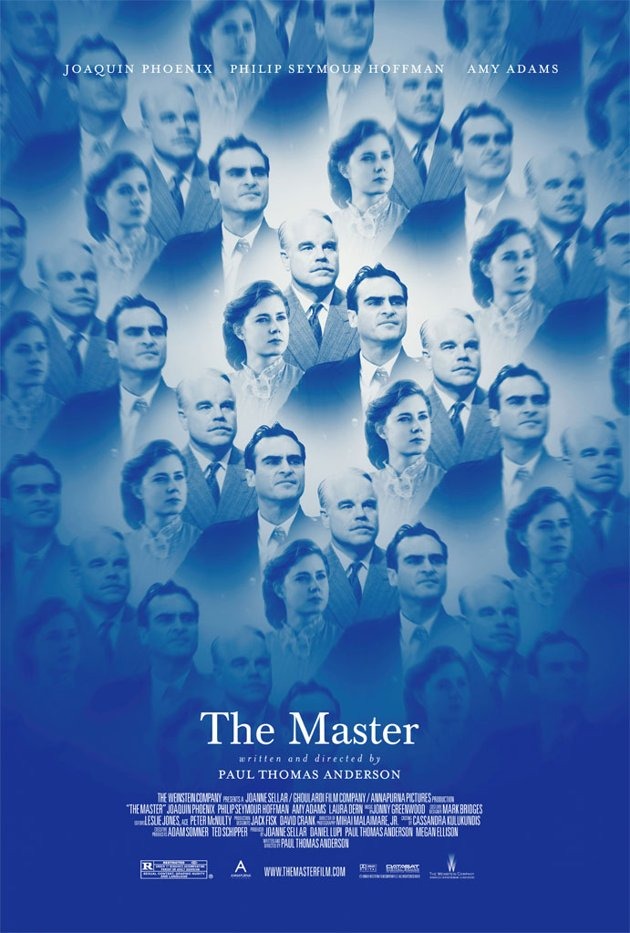

The film follows alcoholic Freddie Quell, a simply impeccable performance by Joaquin Phoenix (Walk the Line), struggling to find a way post World War Two service. He drunkenly stumbles onto the boat of charismatic Lancaster Dodd (a beautifully nuanced Philip Seymour Hoffman (Copoyte, Doubt, Punch Drunk Love)), leader of philosophical movement The Cause.

We will say, The Master is not Anderson’s best work but that is more of a testament to his already impressive resume. However on aesthetics alone, The Master reigns supreme in his canon. Anderson uses a bold and vibrant palate of images ranging from Fordian wide angles, to Wellesian lighting, to Kubrickian set pieces. His meticulously framed shots linger on screen, capturing both the psychotic and claustrophobic nature of the film. Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood returns as composer and produces an even more polished score. There Will Be Blood played in an operatic fashion, emphasizing obsession and decadence while The Master’s plays on a broader spectrum, with wistful melodia articulating biting nostalgia and violently blunt chords conveying mental fragility.

And the performances of this movie are nothing short of superb. Phoenix brings intricacy to a wild and neanderthal drifter. In his incredibly visceral performance, Phoenix sports a drunken slouch; displaying a begrudging patronization of being upright and conforming to societal norms. His performance is mirrored so eloquently in Hoffman’s focused calm, which sits precariously on the precipice of violent outbursts. Amy Adams (The Fighter, Doubt, The Muppets) delivers a ruthless and frightening performance as Dodd’s picturesque first lady.

If the movie falters, it’s that its complexity is dense and confusing. Similar to the rest of Anderson’s work, this movie requires not shortness of contemplation and is far from easily digestible. Scenes and themes are seemingly disjointed and not resolved. But perhaps this is what resolves so nicely in Master: The simple irresolution of two men at such extremes with each other that they are unable to even transform. Audiences are accustomed to likeable people who change themselves through the process of the film. Master refuses this; taking instead two irreconcilable personalities and showing the cracks in their foundations.

There is no fluff in Anderson’s craft. His intensely human themes of alienation, isolation, familial dysfunction, and spiritual queries are deconstructed and reconstructed in oddly familiar, yet novel ways. Few auteurs have the audacity to tackle such meditative questions, and even fewer have the tact and skill to execute them in such a refined manner. That is why we will say it again, Paul Thomas Anderson is a master of cinema.